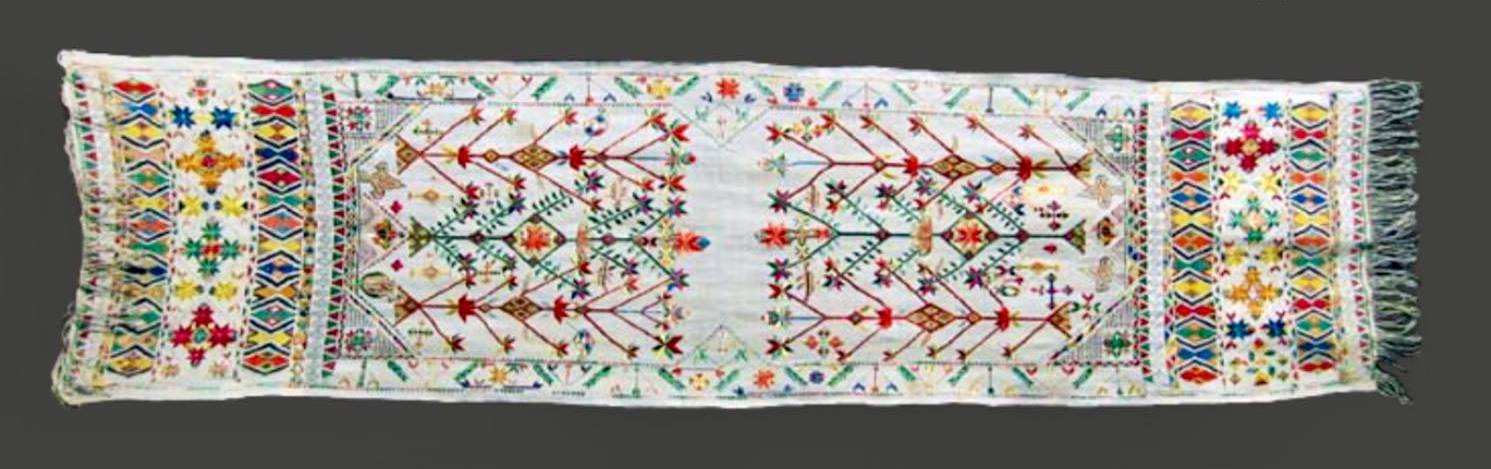

Among the Armenians, the holiday was known under several names: New Year, Taremut, Kaghand, Kaghind, Kalontar. The night before the New Year was known as the Night of Lole, Hlvlik, Kakh, Gotekakh. The latter were determined by folk customs performed during the holiday. Having lost its statehood, the New Year lost its wide public resonance and inclusion in the holiday and gradually modestly “settled” in the family, and partly in the community environment. Only in those provinces where the New Year was still called Navasard (Syunik, Artsakh, Utik, Nakhichevan) and celebrated in mid-November, did it still have wide public participation and was celebrated publicly in open areas with musical groups and entertainment. But family involvement and holiday celebrations were more common. The main symbolic actions were aimed at cleanliness of the body, space and soul (complete cleaning of the apartment and surrounding areas: barn, garden, pantry, replacing old clothes with new ones, using red, paying off debts, transforming hostile or unfriendly relations into friendships or reconciliation, etc.), ritual prevention of evil (use of fiery signs and objects, driving away evil with shots, anti-evil guards at night), ensuring goodness, abundance, family and social harmony, health. On December 31, ceremonial bread was baked, known as “Bread of the Year”, “Krkeni”, “Dovlat Krkeni”, “Kloch”, “Purnik”. Among the pan-Armenian customs of the New Year, one can single out ritual detours of groups of 10-12-year-old boys and, in some places, groups of girls, as well as the tradition of greetings on the holiday the day before. Despite fasting, a meal called “kyashka” or “harissa” was cooked at night: layers of meat and wheat, but they were never mixed so that there would be no unrest, disagreement and anger during the year. It was tasted early in the morning, yet “the darkness was not separated from the light.” On January 1, visitors were bombarded with symbols of abundance: nuts, raisins, small candies. Among the forms of New Year’s holiday entertainment were home games, the play of shadows cast on the wall, riddles, quick games, and visits to relatives. Fruit was very important. Dry and fresh fruits, along with raisins and legumes, were the main components of the New Year’s dish.

The celebration of the New Year in Armenia has undergone significant changes and acquired a public character during the Soviet years. The custom of decorating a Christmas tree has become widespread. Christmas trees were either public (on the main squares of villages and districts, in schools, workplaces, in places of culture – theaters, concert halls), or privately-family. The characters of Santa Claus and Snow White entered the 20th century Armenian New Year. Dishes familiar to the USSR (salads, pastries, new snacks, etc.) also entered the festive life. The popularization of the holiday was also facilitated by new areas of festivals with public and cultural offers (children’s Christmas trees, corporate parties, concerts), and with the spread of television, family gatherings, because it was possible to “participate” in official events remotely without leaving home.

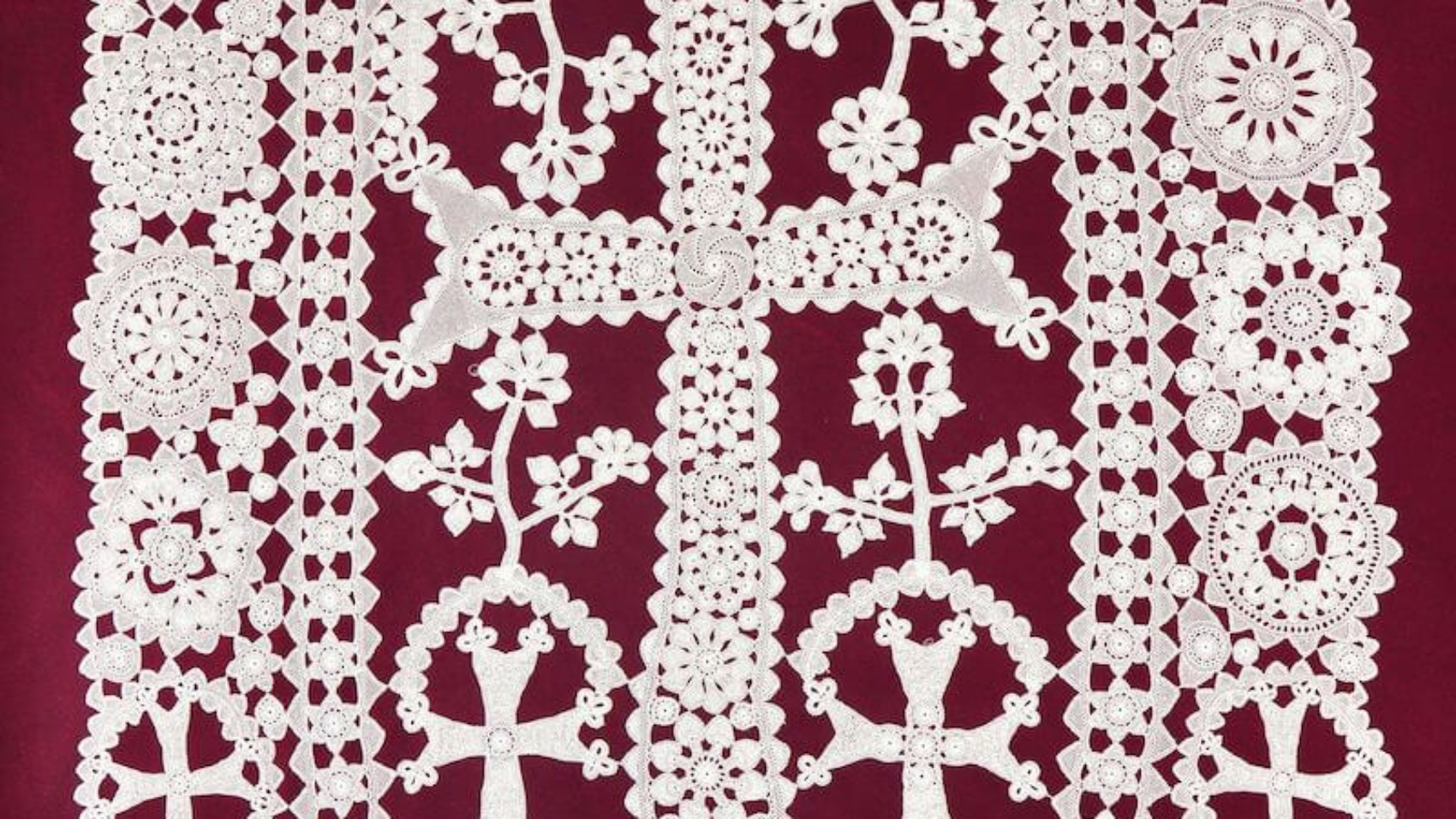

With the independence of Armenia, public relations have left a new imprint on the festival. A new phenomenon is the festive decoration and decoration of settlements with lights and many Christmas trees. The festive decoration of apartments, sparkling garlands, balloons, etc. received a new development. At the same time, the search for the restoration of some traditional national values is intensifying: baking “Annual bread” and other ritual pastries, their ritual cutting-tasting and fortune-telling. The New Year forms a new culinary complex, which includes obligatory (tolma, pancakes, kufta, vegetable salads, legumes, nuts, fruits, gata), desirable (specially processed pork leg or turkey) and updated creative part of the traditional. One of the features of the holiday of the year is that people prepare for it emotionally and financially almost the whole of December, with shopping, advertising of entertainment, service and sales business offers and a sharp change in the assortment of store premises.