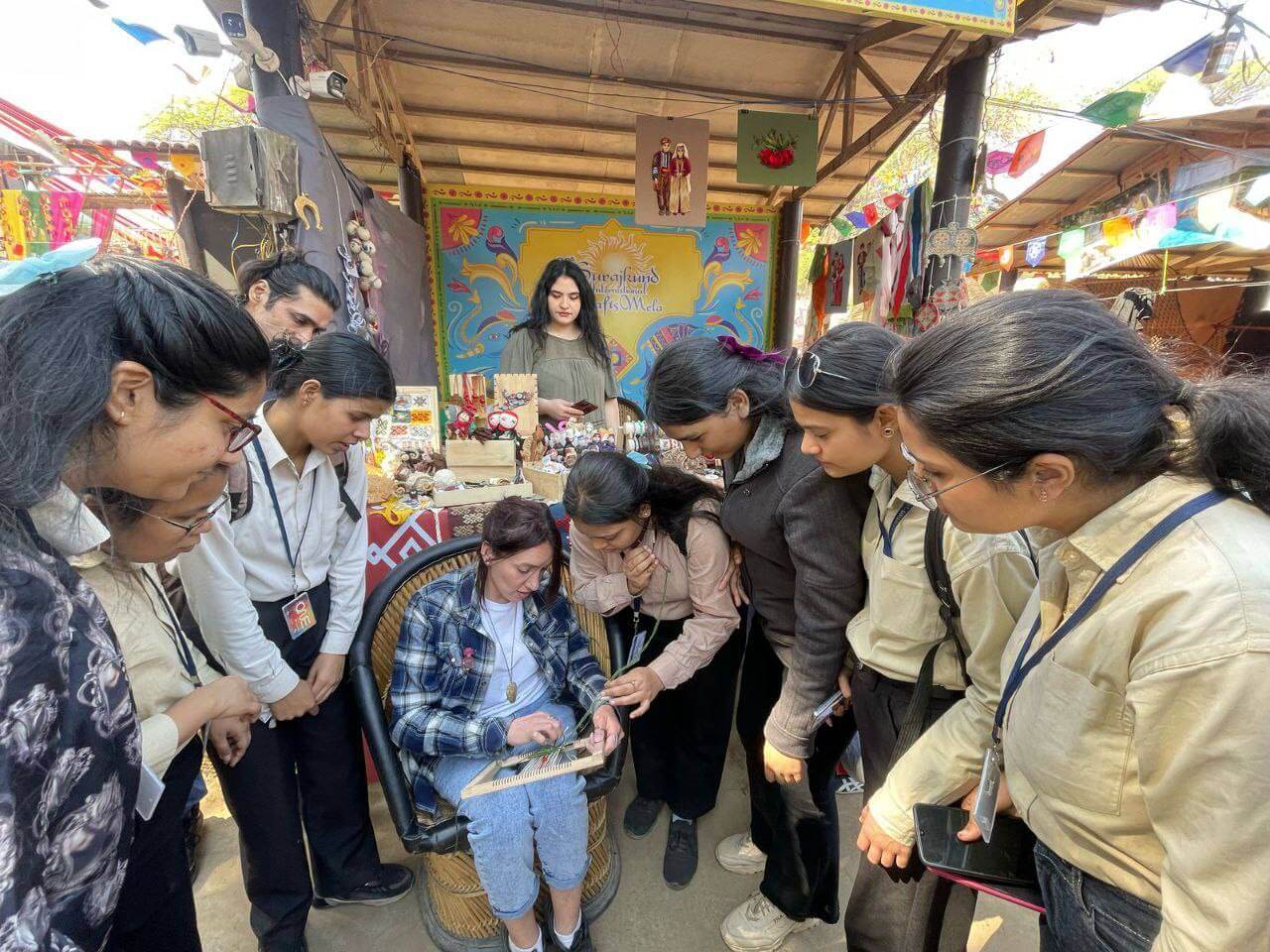

Socks are an essential element of the Armenian traditional costume. Ornamental knitted socks were made in various regions of both Western and Eastern Armenia. The socks in question belong to the category of short women’s socks adorned with intricate patterns. In the 20th century and the early 21st century, Armenian women from the Hadrut region of Nagorno-Karabakh continued to knit a variant known as shatal socks. The name shatal is likely derived from the specific knitting technique used.

These socks required a unique knitting technique and featured complex ornamentation, making them highly valued. They were considered precious gifts and were included in bridal dowries. Before marriage, girls would learn and knit such socks to offer as gifts to members of the groom’s family. Worn primarily during festive and ceremonial occasions, they were richly embellished with detailed designs. In Hadrut, they were knitted from the toe up using two needles. The toe was decorated with “Tree of Life” motifs. The knitting was uniform and delicate. Unlike ordinary socks that could be unraveled and re-knit when worn out, these were more durable due to their toe-up construction.

Traditionally, the yarn was handspun from wool and dyed using natural materials in copper pots: onion skins, madder roots, walnut husks, celandine, and other plants. During the Soviet era, chemical dyes became common, and today, ready-colored woolen yarn is typically used. Mentions of sock-knitting traditions among the Armenians of Nagorno-Karabakh appear in various ethnographic studies. Descriptions of the Syunik-Artsakh costume group often include ornamental socks. It is noted that women knitted while sitting, walking, or conversing, a testament to their skill and dexterity.Numerous ethnographers (A. Stepanyan, N. Avagyan, among others) have explored the symbolism of motifs and colors, knitting techniques, and geographical distribution. Ethnographer S. Poghosyan, in her article “Artistic Features of Traditional Women’s Attire in Artsakh” (Artsakh State University Scientific Bulletin, No. 1, 2022), also discusses shatal socks, noting that in Zangezur and Nagorno-Karabakh they were decorated with hook-shaped and T-shaped motifs. Women’s socks were short, with wide bands and narrow linear patterns, while men wore longer socks.

The sole and upper part of the sock often featured white square motifs. The front surface frequently depicted two birds facing each other and floral designs. The central motif was bordered with an ornamental frame, sometimes including the eternity symbol. The upper part was decorated with diagonal and spiral patterns. In some variants, woven borders replaced knitted ones, and bird patterns were embroidered with floral motifs. These shatal socks were made using needles and crochet hooks from wool, cotton, goat hair, or silk thread.